A jornalista Alexandra Farah, do Filme Fashion, indicou esta matéria do site Guardian Unlimited, sobre a exposição de David Lynch. Achei tão boa que resolvi reproduzí-la aqui. Divirtam-se!

A jornalista Alexandra Farah, do Filme Fashion, indicou esta matéria do site Guardian Unlimited, sobre a exposição de David Lynch. Achei tão boa que resolvi reproduzí-la aqui. Divirtam-se!

Por: Sean O’Hagan

Sunday February 25, 2007

The Observer

David Lynch: The Air is On Fire

Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, Saturday to 27 May

“I am sharing an elevator with David Lynch. The elevator is a small glass cube attached to the exterior of a big glass building, the Fondation Cartier in Paris. We are whizzing silently upwards, the ground disappearing beneath our feet in a way that makes me want to close my eyes and grit my teeth. It is a Lynchian moment.”

Having just surrendered to the three-hour trauma that is David Lynch’s latest film, Inland Empire, it strikes me as slightly odd that a mere elevator ride could ever unsettle a man whose vision is so extreme, so determinedly and brutally dark in its delineation of psychological breakdown. Indeed Inland Empire is such a strange, labyrinthine, relentlessly disorienting experience that you wonder, not for the first time, whether Lynch himself might just be a little unhinged.”

“A producer once called Lynch ‘Jimmy Stewart from Mars’, and that description still holds. He is perhaps the only person I have ever met who manages to come across as simultaneously utterly relaxed and deeply intense, though this may be a side effect of his long-term devotion to Transcendental Meditation, to which he is deeply committed. ‘It’s the ocean,’ he says at one point, making a circular movement with his hands, ‘the big ocean right at the source of thought. Any human being can dive in, and transcend. It’s not a sleepy thing, it’s powerful. Energy, energy, energy.'”

“We have met to discuss his extracurricular creative pursuits, which include photography, sound sculpture, painting, drawing and what might best be described as doodling. Even David Lynch’s doodles, though, are disturbing. From Saturday, the Fondation Cartier is hosting a huge retrospective of his art work entitled The Air is On Fire.”

“Lynch started out as a painter at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art way back in 1966, and famously moved to making short abstract films, which he calls ‘moving paintings’, when he saw one of his canvases moving in the wind. With the money he made from his first private commission while still an art student, he bought a Bolex Super 8 camera. Given the almost accidental nature of his move into film-making, would he ever have been satisfied had he remained a painter? ‘Oh yes,’ he says, without hesitation, ‘for sure. That’s all I wanted to do for a long time. Just paint. But, suddenly, now there was film. This big thing.'”

“The ground floor at the Fondation Cartier is devoted to Lynch’s paintings and drawings, the latter of which number in the region of 400, and some of which seem to date back to his college days. ‘I hadn’t seen a lot of this stuff for a long, long time,’ Lynch drawls, ‘and it made me realise that it’s actually a very good thing to see old work again. Some of the stuff that came out of storage really fired me up. I really don’t know where it will lead but it sure feels good.'”

“Over the last few years Lynch has been painting several series of nightmarish landscapes, each peopled with vague shapes in opaque, dusky landscapes. One such series is called The Mr. Jim Series; another, The Bob Series, perhaps inspired by his love for the Bob’s Big Boy restaurant in Los Angeles where he used to breakfast daily on ‘four, five, six cups of coffee – with lots of sugar’. He’s since given up sugar as a creative catalyst but his vision remains somewhat frantic. We both stare at a work called Bob Burns Tree. I ask him to talk me through its gestation.”

“‘Well, it’s called Bob Burns Tree,’ he says, pointing to the Bob figure and then to the tree. ‘I knew from the start it was going be about, well, Bob burning a tree. I started with that idea and I kind of stayed with it. Yep.'”

“That’s cleared that up, then. Does he concern himself with traditional notions of, say, composition and colour? ‘Well, you don’t think about it, no, but it’s there. It’s not an intellectual thing. It’s an intuitive thing. I mean, I don’t think you could teach that, really. There’s billions of variations on a theme of composition. Just infinite. It’s just a thing that’s there. It just, um, starts feeling correcter and correcter until it’s done.'”

“We stare at another big recent piece called Do You Want to Know What I Really Think? The words are coming out of the mouth of a squat, evil-looking man holding an object that might be a tiny gun. He is standing opposite a seated woman who is naked save for what looks like a pair of men’s underpants wrapped around her knees. Formally, it is what used to be called a mixed-media painting: the backdrop is a photograph which has been digitally manipulated, and on which Lynch has placed the two photographed figures. They, in turn, have then been painted on, as well as having bits of actual fabric glued to their bodies. ‘Lotta glue,’ says Lynch by way of elucidation.”

“I tell him that it looks, like many of his paintings, somehow definably Los Angeles, though I am not entirely sure why. He seems pleased with this. ‘Oh yeah,’ he says, emitting a strange Beavis and Butt-Head-style laugh. ‘This is a Los Angeles painting all right. For sure.'”

“The basement floor is given over to Lynch’s photography, which can more or less be divided into three categories: ‘Nudes’, ‘Factories’ and ‘Melting Snowmen’. This being David Lynch, the nudes tend towards the uneasy and disturbing, while the snowmen and the factories tend to be oddly calm and relaxing. In a series called Distorted Nudes, he has digitally manipulated Victorian erotic photographs into strange shapes, some of which resemble the brutalist torsos of his hero, Francis Bacon. He once described Bacon as ‘to me, the main guy, the number one kinda hero painter’.”

“In the Factory series, Lynch peers with his camera into the darkest corners of deserted industrial buildings, somehow poeticising stained sinks, rusting signage, dismembered pipes and the like. Everything is shot in close-up and printed dark. The result is a recognisably Lynchian world, perhaps the one you hear but don’t see in his first feature film, the still unsettling Eraserhead”

“‘Industry!’ he says, relishing each syllable. ‘In photography, it often seems to me, that all you need is just a word. It could be as simple as the word “industrial”, and that just fires you up to go to different places to see what industry is giving you. Then it’s about the way the light goes, the shapes, the decay. These big, beautiful things and how they are being eaten by nature. That’s just incredible, beautiful, unreal.'”

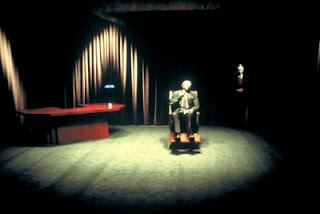

“Downstairs, too, there is a small cinema, also designed by Lynch, which will show his early short films: The Alphabet, The Amputee, and The Grandmother, but not, alas, Six Men Getting Sick, which he once memorably described as ’57 seconds of growth and fire, and three seconds of vomit’.”

“Lynch’s paintings and drawings are strangely lacking any discernible style, unlike his photographs which have his definable signature. Some paintings seem almost constructivist in their deployment of geometric shapes and random squiggles, while others seem simply to be frames from the story boards of films such as Blue Velvet and Fire Walk with Me. They are unified only by the strangeness of their subject matter, and, in places, recall the work of Outsider artists such as Henry Darger or Bill Traylor. Lynch obsessives will love them, but I much preferred his photographs, particularly the beautiful and disturbing Distorted Nudes series. As a photographer, at least, he is a surrealist.”

“I ask him whether he finds painting and film to be almost contradictory processes, the one intimate and singular, the other collaborative and doggedly single-minded.”

“‘Well, to me, they’re both intimate and singular. With film, you just have a crew and actors around you all the time, but the thing is to bring them along with the idea that is driving you. You stay true to the idea the same as you do with a painting. With film, you fall in love with an idea, you stay true to it, and you translate it into cinema, and you don’t walk away from any element of it until it feels correct. Then, you just hope it feels correct to others, too.'”